Just a reminder, while this isn’t a “what does it all mean?” post analyzing the plot of B.I., I cannot avoid some spoilers. I also have some mild Inception spoilers, so if you haven’t seen that yet, go find out why all the critics were wetting themselves in 2010. I’m going to hit the ground running from Part one without any recap, so please check that out before digging in here if you haven’t already.

So what makes art “real art” anyway?

I mean besides the fact that these champions of bourgeoisie aesthetic say that it conforms to their ethnocentric and back-in-the-good-old-day, past-revering sense of artistic merit—mostly because that’s what their professors taught them? Is it simply a completely subjective matter of opinion? Or is there a reason that people the world over and from many different cultures seem to have a general level of agreement about a lot of good art. What is it that makes art connoisseurs mouths go dry—whether schooled in New England or Uganda or Tokyo—when they look upon the statue of David.

I mean…besides his peeper, of course. Magnificent.

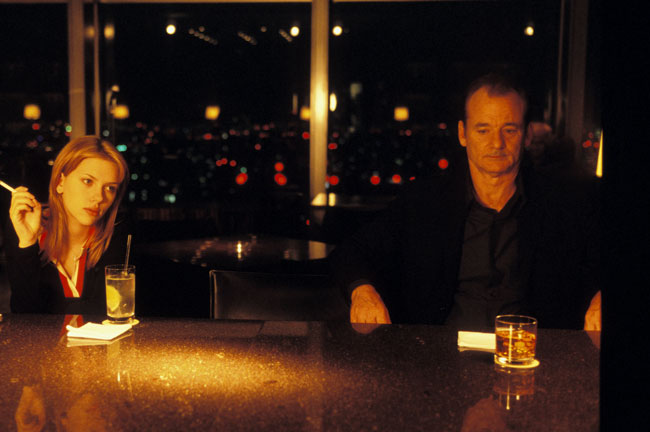

|

| The Editor tried to put a picture here. It wouldn't work for some reason. |

Is there some way to consider an offering of something totally new to the artistic world without getting a million people to upvote it on Reddit, or calling up your old Humanities professor? Can an individual human look at some bit of art and decide if it is good at some level beyond their personal opinion?

“What is art?” is a complicated question wrapped up in the philosophical idea of beauty, and there’s no way anyone can definitively answer it—especially not while keeping geeky and making lots of jokes.

The good news is that I don’t have to.

While are problems at either end of the spectrum of “art is only narrow definition X” vs. “art is totally subjective”, and a large grey area of personal taste in the middle, there do tend to be certain factors that consistently play into art crossing the “real art” rubicon, in a way that most people agree with most of the time. We don’t need to spend a lot of time examining what the murky grey area between art, “high art,” and consumable entertainment. We can just look to see if the art that most people agree is fabulous has certain commonalities.

And it does:

1) It is technically excellent. Not “technically” as in “really, truly, by a technical definition”. (Such as: “I technically didn’t drive your car, dad. I just sort of steered it while it rolled down the hill.) Technically as in the technique of its execution. If it is writing, it is very great writing. If it is painting, it is masterful painting. If it is sculpture it is nearly perfect. If it is film, it has seamless editing and audio visual elements. Whatever the art is, it’s execution borders on flawless. Or at least as flawless humans are capable of.

2) It has subtext. Whatever the form of art, it goes beyond itself, with a meaning that is greater than it’s absolute. It’s gestalt is greater than the sum of its parts—even if not explicitly in the mind of the artist during creation. There are things within the art that mean more than simply themselves. In a video game, as in a movie, this can take place by means of symbols in the visuals, subtext in the dialogue, or both.

3) It is relevant. Yes, the old famous “human condition” that has become a cliche of art departments round the world for the frequency of its parroting. Good art touches something within us in its examination of humanity. It can be politically relevant (though rarely does propaganda make for “real art”) socially poignant, or simply an expression of our longest standing philosophical struggles with our own existence. But at some level the art explores something about humanity that we all share. This is why, within science fiction, infinite Star Wars clones fail to impress most “high art” sommeliers, but Ursula Le Guin and Phillip K Dick are hailed as being literary.

4) The composite elements that make up the art form help reinforce (either by working with or through the relief of contrast) a thematic vision of the art itself. This is a little harder to explain. Basically every art has elements that make it up. Painting has color and texture and form and content and imagery. Literature has setting, plot, character, tone. Film has cinematography, soundtrack, acting, costuming, and visual effects. In many arts these elements themselves have further elements (like cinematography has lighting, focal points, composition and such) that all lead up to a massive composite of skill and artistry (or not) within the final work. If this artistry is haphazard the work can be technically proficient, relevant, and have subtext, but there is a strange discordance between the elements. When art is “good art” these elements work with some of the work’s central themes and form a cohesive vision.

Consider John Steinbeck, an author I picked because most Americans have read at least some of his work. You probably had to do some homework at some point about how Steinbeck’s settings always mirrored the psychological struggle of the characters within the chapter. Rooms with old lamps that caused one half of the room to be lit and the other half to be in shadow became chapters where both the best and worst of humanity was revealed. Steinbeck constantly used his settings as a kinetic landscape for the themes he explored.

However, this idea may be easiest to demonstrate rather than explain. Take the example of Inception. Critics went crazy over this soundtrack and it was nominated for the Academy Award for best original score (though it didn’t win). Here’s one of the best songs in that soundtrack:

It’s a simple song, reiterating a single theme over and over, but at each new iteration it adds in a new layer of instrumentation. Most of the score involves songs that are very similar in execution. This is actually a pretty basic and overdone musical technique called “looping.” It’s considered to be pretty uninspired most of the time. Why did critics like it so much for Inception? Because that layering effect both increases the complexity of the score and adds to the sense of danger….

…in an exact mirror of the movie itself.

At each level of the dream, a new layer of dramatic problem was added and the stakes increased.The music was a perfect reflection of the themes of the movie. Also, the movie itself was exploring the way that once an idea gets into your head, it goes around and around picking up steam—much like the songs themselves were doing—becoming louder each iteration. The soundtrack represented and enhanced the movie’s themes.

So those are the four elements. They aren’t comprehensive, and there’s a lot of room for personal aesthetic, but the works consistently deemed to be “high art” tend to have these things in common.

In the interest of full disclaimers with my list, I should say that sometimes art—great art—doesn’t have all of these elements but excels in the others especially given its place in a post-structuralist context. The statue of David doesn’t have a lot of subtext per se, but it fulfills the other aspects so thoroughly that it cannot be discounted as a phenomenal work of art.

This is why Star Wars is always listed as one of the greatest films by all but the most snobbish of film critics—even though it gives most literature professors an aneurism in their brain to think about it. That movie is breathtaking. The flawless execution (for 1977) of audio and visual effects was a masterpiece, and every single frame reinforced the thematic core of good versus evil, from the costumes to the music to Han’s divorce from moral ambiguity at the end. And though it took a generation to consider the historical context of Star Wars, we now appreciate its response to a post Vietnam era world where culturally there was a lot of anxiety about good and evil and if either of those things were real forces in the world. George Lucas gave us that world in a space opera steeped with mythological subtexts.

I will leave others to nitpick Bioshock Infinite’s technical excellence if they wish. I am neither a game designer nor a programmer, and I can’t really say if there were mistakes (as such) in its execution.

I will say this: I have played perhaps 50 games per year since I was five or six. So that’s like…um…carry the two…uh…a lot of games. I fought my first-grade friends with bouncy bullet tanks for a victory in Combat on my Atari. I got the Triforce and rescued Zelda back when that was an 8 bit quest—(and again at sixteen bits, and again at 32….) I’ve played every iteration of Final Fantasy (except the first). I have hunted the giant boatfly in the DLC of Fallout: New Vegas. I know the pain of the jumpy parts in Castlevania, and the triumph of beating the C&C General’s boss on the highest difficulty.

If gamer dudes look at me and say “Do you even game, bro?” I have the honor of stoically nodding my head like the grizzled veteran I am.

My sense, as an experienced gamer, is that Bioshock Infinite was as close to flawless as I’ve seen a game. I have been watching acting in games since Malcolm McDowell blew us away as Admiral Talwyn and listening to non midi soundtracks since, I bought my first 3DO nearly 20 years ago now. I was there when the chill went up the collective spines of gamerdom as we realized that there was a choral accompaniment for the battle with Sephiroth. I was there when we had to plug our controller into the second player slot to beat Psycho Mantis. I was there when the mountain began to move and the fight with the first Colossus began. If there’s a game with a markedly better technical execution in terms of graphics, voice acting, or soundtrack, I’ve not seen it.

In the next section of this article (which may go on a bit longer than five parts, now that I’m in the middle of writing it) I will examine one of B.I.’s most nagging philosophical questions as well as show how its internal elements reinforced this theme.

CONTINUED IN: Part 3

Writing About Writing An irreverent, funny, and at times poignant blog about writing....and sometimes cheese.

No comments:

Post a Comment